AWS Resilience Series - Availability vs Recoverability

Note: the following post is going to focus on AWS in any discussion of examples, but the overall concepts here are meant to be vendor-agnostic and can be applied to any cloud environment.

One of the biggest points of confusion I've run into when working with teams on their resilience strategies in the past is the difference between (high) availability and recoverability. I don't blame them, lots of the buzz around cloud apps focuses on building things that are highly available and often eschew the notion of recoverability entirely. I mean sure if your service never goes down, then there's never anything to recover, right?

If there were true, I'd stop writing here and you all could close this tab and return to your regularly scheduled cat videos. You could certainly do that anyway, but when your video is over I'd recommend maybe coming back here and making sure you know how to keep those cat videos rolling even on the rainiest of days.

The Shared Responsibility Model for Resiliency

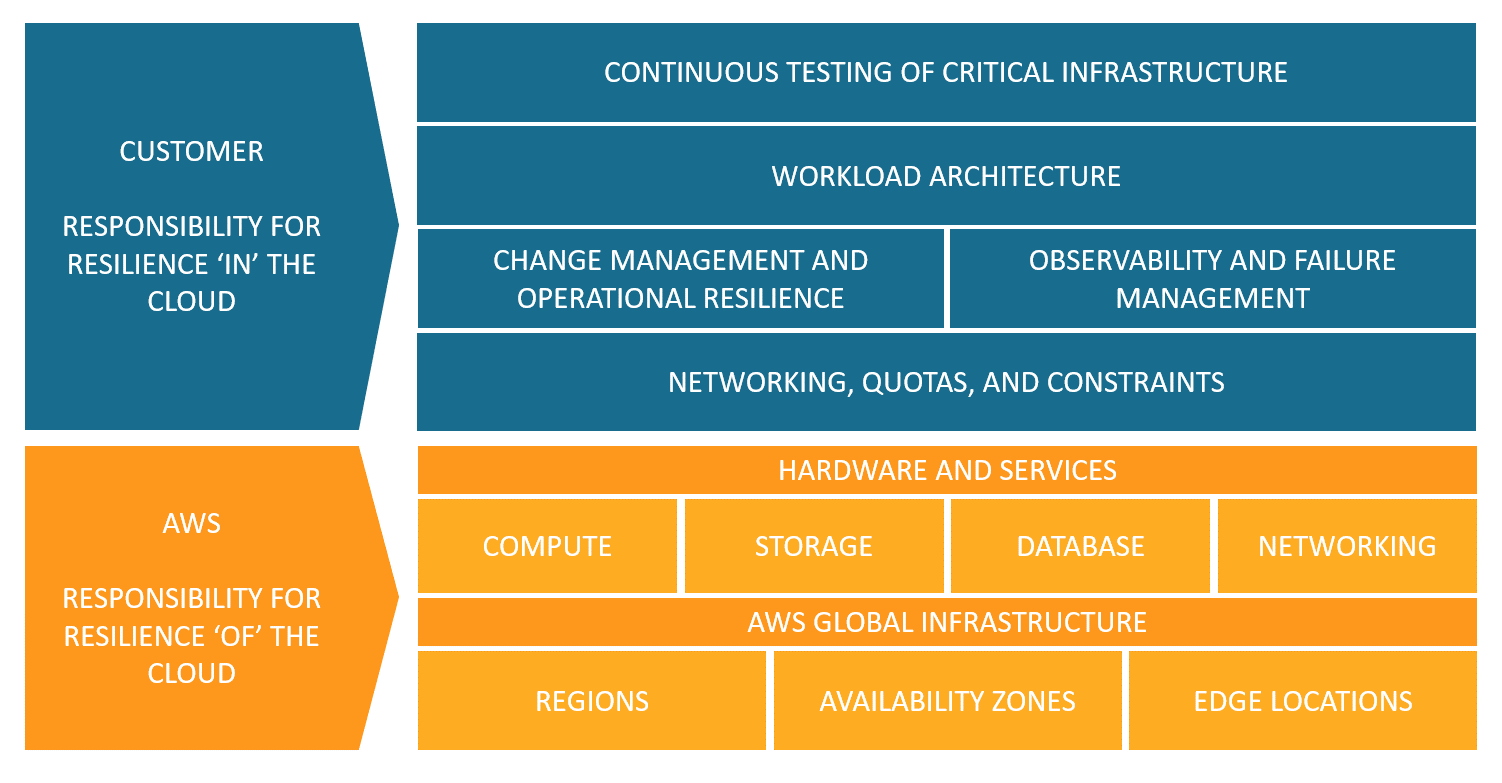

Before we get into the differences here, I think it's important to start with the Shared Responsibility Model for Resiliency.

If you've worked in AWS for a while, you're probably aware of the Shared Responsibility Model in the context of security. The resiliency model is thematically similar: AWS is responsible for the resilience "of" the cloud, while us as the customer are responsible for the resilience of our workloads "in" the cloud. I like to start with this because it helps to set the stage for debunking some of the myths around cloud resilience that can leave you in a tough position if you're not prepared for a disaster. The biggest culprits here are the durability and availability guarantees provided at the service level.

Let me be clear that I'm not intending to imply that AWS (or any other cloud vendor) is attempting to mislead customers. The opposite is actually true, the fact that S3 has a 99.999999999% durability guarantee is an incredible feat of engineering that should be celebrated! But when using S3 keep in mind that the durability guarantee serves AWS' side of the shared responsibility model - it's extremely unlikely that data stored in S3 will be lost at the fault of AWS. So our data is all safe in S3 and we don't need to worry about it, right...?

Not quite. If you read that sentence over again, you'll notice that I said "...at the fault of AWS". Those impressive durability numbers will do nothing to protect you against a catastrophic bug in your code, ransomware attacks, or simple human error of your users or someone on your team. These types of failures fall on your side of the shared responsibility model, and directly impact the recoverability of data in your application.

There's a similar comparison to be made on the availability side of the equation with the various service level agreements (SLAs) that apply. For example EC2 has an instance-level SLA of at least 99.95% uptime, but that SLA does not apply to scenarios in which your instance fails due to something on your side of the model. An example of this could be your workloads exhausting the available memory on and instance and causing a crash, or a security vendor pushing an improperly tested patch to your machines.

Availability

"High Availability" is one of the big buzzword concepts of modern cloud architectures. This is for good reason - the commoditization of compute resources has made it really easy to simply run more instances of your workloads to ensure that there's always a node available when needed. The cloud made it so that suddenly we could solve all sorts of performance and availability problems by simply throwing more computers at them. Sure you can make an argument that this has made it easier to write software poorly, but there's no denying that the ease of scale provided by cloud computing is a net-positive for service availability.

Beyond sheer scale, cloud computing allows us to put our workloads in geographically disparate places which has its own share of benefits. By changing just a few lines of code, AWS (and other cloud providers) allow us to spread our workloads across different physical locations, insulating catastrophic failures in one location from impacting our workloads in their entirety.

I could (and will) write an entire post on the different types of fault-isolation boundaries provided in AWS. For the purposes of this discussion however, it's important to consider that you generally want to reduce single points of failure in your applications whenever it's possible and feasible. This means running more than one instance of any compute resources, and at least leveraging database configurations that maintain availability across multiple zones. For data, this usually comes with some amount of replication as well to ensure that there are multiple copies of your data being kept synchronized and ready for use should a primary dataset become unavailable.

The extent to which you configure your resources to be highly available has a direct correlation to your bill, so there's a constant balancing act to be performed to ensure you're not overspending but also not underdelivering on availability.

Recoverability

If high availability is one of the hot buzzwords of cloud computing, recoverability is the complete opposite in that it's often ignored (or at least under-appreciated)! Despite this, I'm of the opinion that recoverability is actually more important for most workloads.

At the most fundamental level, recoverability is your ability to restore your workload and its data from any sort of incident which might cause it to be inconsistent with its desired state. For your running application, this can be a crash or performance degradation due to resource exhaustion, operator error, or a bad code change. For data, this can be data loss due to inadvertent deletion, ransomware (or some other security incident), or even accidental modification. In either scenario, it's important to keep in mind even the seemingly infinite realm of the cloud, there is still physical infrastructure behind the scenes that's susceptible to catastrophic failure.

Put simply: when something bad happens, recoverability represents your ability to make things good again.

In a world where businesses are placing huge values on their data (and in many cases, data can be quite literally everything to a business), it doesn't matter how available a system is if the data contained within it can be lost at a moment's notice. From a data perspective, recoverability usually comes in the form of backups. It might be tempting to think that your data backup needs are covered by synchronized replicas (surely you've just finished reading the section on availability, right?). Yes, synchronized replicas do increase availability and durability (which serves the AWS side of the shared responsibility model!), but since they're synchronized it means that any failure condition of your data is immediately replicated to all of your copies. That table you just accidentally dropped in production was dropped from every replica within milliseconds, leaving you with just as much of a mess to clean up. To truly recover, you must have some sort of backup of that data that you can restore.

If there's one thing you learn from this entire post, let it be this: like RAID, replicas are not backups.

Recovering compute is a different conversation entirely. Thanks to the "treat your servers like cattle, not pets" analogy and the prevalance of twelve-factor methodologies, modern cloud applications typically are built such that compute is fungible. That's to say: if your server somehow fails, you should be able to recover it by simply deploying another one. If your application is built in such a way that losing your compute is anything more than a minor annoyance, you may want to consider why that's the case and seek ways to improve your architecture. The best-case scenario (besides no failure) is that automation has you covered and compute is kept healthy without any intervention; this is overlapped right into the high availability camp. If you cannot get to that point for some reason, then you want to at least make sure any manual interventions are as quick, easy, and repeatable as possible. Automate and script as much as possible to minimize any potential for human error.

Putting it all together

By this point I hope that it's clear that availability and recoverability are two separate but intertwined concepts. Well architected cloud applications need to consider both, especially when your application's data is business critical. Remember that it's easy to get lulled into a false sense of security by high durability numbers and an architecture that scatters replicas of your data across the globe.

Always ask yourself: what would happen if I woke up and this data was gone tomorrow? If the answer is anything besides "nothing", back it up (and then maybe copy that backup somewhere else, too). Of course you should also be doing Well Architected evaluations periodically, which includes the Reliability Pillar that covers this and more.

Overall building highly available systems is a desirable trait - your systems should be available whenever a user needs them. Just keep in mind that even highly available systems can and will fail at some point, at which time the ease and efficacy of your systems' recoverability are far more important than any availability feature it has.